These are the three questions I answered, or rather, to be in keeping with the rhetoric of exams, and to be honest to my own performance, attempted.

3.Anna Barton describes 1 Henry IV as a play 'in which comedy continually tests itself against historical truth.' Explore this perception.

18. ''He is not to be taken as a playwright who opens up a complexity of Elizabethan attitudes...but is stuck with the responsibility thrust upon him by Jonson in a commendatory poem prefacing the 1623 folio of the plays: 'He was not of an age, but for all time!'' (Gordon Williams)

How would relieving Shakespeare of this responsibility affect your reading of any one or more of his works?

22. Consider the role of pregnancy in at least two of Shakespeare's works.

Labels: exams, Shakespeare

The Renaissance theatre however, was radically different. In 1647, a Puritan government stopped all theatre, worried about the state of the degraded theatres and those who frequented them. The dramatic zeitgeist of Shakespeare's world was just as highly charged, but with a deep complexity running through it. Here, drama was not absolutely forbidden, but it was subject to censorship, and to a set of received wisdoms about what a play could or could not contain. Involved in a constant dialogue of negotiation, the Elizabethan stage particularly was an arena of political power, which at once threatened and confirmed the monarch's power. I'll consider (briefly), how Shakespeare's plays were involved in this complex positioning.

Ben Jonson observed of Shakespeare that he was 'not of an age, but for all time.' Do historicist critical approaches to Shakespeare undermine Jonson's sentiments?

Jonson's line, from an Epistle in the First Folio, presents us with a binary choice - Shakespeare is either grounded in his time, or transcendentally applicable to any time. But the interrogation of Shakespeare's cultural, economic, and political background doesn't have to be a divisive issue - the study of Shakespeare in his 'age' can be enlightening not just on the text situated in its historical context, and also on our own reception of him. Brecht's engagement with Shakespeare was unashamedly historical - he insisted the minutiae of costumes be perfected to match contemporary specifications. The thinking was, the shock of this spectacle would lead act as the verfremdungseffekt, forcing us not only to look critically at the powerplays of the narrative, but also at our own political positions. By emphasising the historical, we at once create a more distant observational point from which to make judgements, whilst simultaneously bringing us closer to an integrated, understanding of Shakespeare's, and our own, societies.

Since we started with the Lord Chamberlain, it might be worth taking him as a departure. The Lord Chamberlain, a prviledged and senior position in the Elizabethan Privy Council, was a powerful figure, and it was the Master of the Revels, a position under the Lord Chamberlain's command, that was responsible for the prevention of seditious drama on the Elizabethan stage. In A Midsummer's Night Dream, Philostrate who takes that role, the 'usual manager of our mirth.' His place is explicitly made as Master of the Revels in the play's dramatis personae, but the same figure appears through Hamlet, who stages his 'Mouse-Trap' play, in an attempt to discover the proof of the King's deceit:

King: Have you heard the argument? Is there no offence in't?Hamelt proclaims the play's innocence, knowing full well its dangerous content, and says as much in a witty play on the word jest - for as much as the play is a revel, it's also a poison that may be 'in-jest'ed, just as the poison on the stage is. The play is a radical space, where the revolutionary material on stage is a clear inditement of the King's guilt, whilst it also pleads its innocence, maintaing that, as a fictive arena, nothing on the stage should be taken too seriously.

Hamlet: No, no; they do but jest, poison in jest; no offence i' th' world.

But that's exactly what does happen throughout the Elizabethan period. Richard II, probably first came to the stage in 1595. Chronicling the deposition of the incumbent King by the rebel Bolingbroke, the play is, of all the histories, probably the most politically loaded in terms of its content. Shakespeare seems to be aware of this. The deposition scene, so crucial to the play, does not appear until the fourth quarto, which is published in James 1'st reign, clearly too suggestive for Elizabeth's stage. And yet, the play maintained the actual murder of the King throughout. That the deposition scene was censored and not the actual murder goes some way to proving just how dangerous symbolism in Elizabethan England could be, the performative act of deposition somehow as dangerous as the performances which were held on the stage. There is also some evidence for Shakespeare's careful editing of the play as he constructed it. In Richard II, Shaespeare has John of Gaunt pronounce a distinctly pro-monarch soundbite, which has no basis in the Holinshed source of the play:

Let heaven revenge; for I may never lifeAnd well he does to be on his guard, because there are certainly resonances of Eliabeth's rule throughout the text. After the death of Gaunt, Shakespeare has Lord Willoughby complain of the taxation on the land:

An angry arm against his minster

And daily new exactions are devis'dThe use of that word 'benevolences' refers to a specific type of tax, which sits anachronistically in the play - benevolences did not exist under Richard II, but under Elizabeth they were one of a number of taxes that led to charges of over-burdening the taxpayers and nobility of the land. Similarly, the 'Reports of fashion in proud Italy', that York complains about sit out of place in this chronicle - Only under Elizabeth did the Italian style become de rigeur for aspiring English dandies - during Richard's rule it was the French who were the model of taste in England.

As blanks, benevolences, and I wot not what

Of course, it would only be later that the true politicisation of Richard II would come to show, as the supporters of the Essex Rebellion paid for a private performance of the play, at a rate of some 40 shillings over the normal price. Elizabeth's political nickname was Richard II, and on a number of occassions we have records showing her councillors using the term. The Lord Chamberlain, considering his relative effecement in the court recorded that he was 'never one of Richard the Second's men', and the Francis Knollys, complained to Elizabeth's secretary that unless his good advice was taken, and he acknowledged, then the Queen would quickly find her court 'play the Parte of Richard the Second's men.' Both men were relations of Essex's. Elizabeth herself seems to have been concerned with the prospect of the play performed 40 times 'in open streetes and houses.' And there is a hauntingly ambiguous line in Richard the II, which retrospectively reads very suggestively. 'The king is not himself' we hear, when the king falls unwell. But perhaps, he is also Elizabeth. Essex was executed the same month as the play was performed for Essex's men.

In comparison, John Hayward, who wrote a chronicle in 1599 about the usurpation of Richard II, with a dedication to Essex was locked in the Tower for a period. Under James I, he was knighted. The vicissitudes of life under different morachs is clear - but so is the threat of the stage. It's seen as an immediate and present danger, in comparison to the mode of the chronicle. And the chronicle as a mode as important roots in Tudor history, where it represented not so much a way of seeking causal relations, but analogous ones. D. R. Woolf considers that Renaissance readers understood history not so much linearally as 'sideways.' Plays were important political tools, both of supporting the dominant culture, and of subverting them. And as Fitzdottrel cenfesses in Jonson's The Devil is An Ass, the play book often seems more 'authentic' than the chronicle. As the study of history, and the development of the artes historicae came about, there was a move to resite history as a study closer to how we see it today. These developments loosened rather than sharpened conceptual ideas of what history is, until the flashpoint of the late 1500's and early 1600's, when drama could act within ever looser boundaries with history plays.

If Richard II offers the most obvious view of the realpolitik associated with Shakespeare's drama, his first, last, and only Jacobean history play offers a more conceptual consideration of history. Originally called All Is True, Henry VIII even from its title asks considerable questions about what historical truth might mean. Does the title suggest that all is true, in a kind of arch-relativistic sense, or that all is true that is to be presented on the stage before the audience, in an antithetical statement. In one of the opening scene of the play, this problem manifests itself, as the Dukes of Norfolk and Buckingham discuss the recent peace-making at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. From the beginning we are wary - Buckingham states that 'an untimely auge' prevented him from appearing, though we know he was present in reality. And Norfolk's description of the event is a complexly ambiguous piece, which reveals further intricacy each time we read it, an artful piece of time-release poetry', and Julia Gaspar aptly puts it.

Consider the two monarchs in the Field:

The two kingswhat Norfolk creates is a dazzling piece of relativism, the two kings set off against each other in a feedback loop of mutual lustre. 'As presence did present them both', immediately conveys a sense of contingency to the laudatory tone of Norfolk, and the sense that the description he offers sits in a kind of vacumn. And the high praise offered soon falls flat. We hear how the talks have been a failure, the King of France moving away from them, and even Norfolk alters his mind, admitting:

Equal in lustre, were now best, now worst,

As presence did present them: him in eye

Still him in praise; and being present both,

Twas said they saw but one

Grievingly I thinkA 'fresh admirer' of what he saw, Norfolk's admiration retrospectively modulates its sense, from an appreciation of awe, to a juxtaposition of reality and dream. Shakespeare makes a reference back to the contingency in the details of the report as well by playing a clever sonic trick in the opening description of the scene:

The peace between the French and us not values

The cost that did conclude it.

Those suns of glory, those two lights of men,I think this is a subtle and playful retrospective. Shakespeare visually and phonically creates the suggestion, between 'Andren' and 'Arde' of Arden, the pastoral forest of play of As You Like It. Another forest in Warwickshire, transported to France, the Arden forest seems an appropriate look back to his former work, and to the dangers of placing too much faith in rigid, objective, realities. Especially on the page, the dash falling after 'Arde' seems to make it unfinished, calling for the final consonant which would make it familiar to Shakespeare's readers.

Met in the vale of Andren.

NOR: 'Twixt Guynes and Arde -

In case you hadn't figured it out, I just wrote this as a bit of revision, and it's now midnight, so I'm stopping. It was fun while it lasted though. if you get this far, have a cookie. Good night!

Labels: renaissance, revision, Shakespeare

Labels: cambridge, jesus college

Labels: cambridge, jesus college

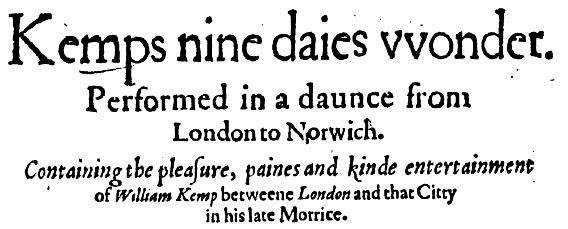

So, Kemp is a big deal. I'm just going to pick up on probably the best thing (subjective) he ever did, and, I might add, anyone ever did. Not content with playing clowns or composing jigs, Kemp had a masterstroke. Why not go on tour? But would a simple tour be enough for Kemp? Oh no. A self-publicist as well, and famous for his engagement with audiences, a simple tramp through England wouldn't really do it. So what does Kamp decide to do?

He spends nine days (with considerable breaks - clown he may be, athlete he is not) travelling from London to Norwich. It's worth adding that, counter to today, where Norwich would not be a remarkable entry in a list of, 'least remarkable places in Britain', Norwich in the late Elizabethan period was England's second city. So a pilgrimage between the two most important cities in England seems a good idea - plenty of urban culture vultures to appeal to for support. But Kemp goes one better.

He does the journey on foot. But instead of walking, he morris-dances. The whole way.

There he is, kitted out in all the latest gear, with bells on. No, literally, with bells on. Note that he doesn't really have a think, pubic-hair-like beard, it's just the fault of the Bodleian's copy of Kemp's record of the event. He dedicates it to Queen Elizabeth, which is thoughtful, because, along with her virginity, the cult of Gloriana, and a bit of a shine for the Earl of Essex, Elizabeth will always be remebered for her insatiable appetite for morris dancing. If the idea itself wasn't bizarre enough (and perhaps if it isn't, you can suggest something to trump Kemp's dance-a-thon) his documenting of the event is equally profound. I enclose a section from his ninth day, as he enters Norwich:

It was the mischance os a homely maide, that belike, was but newly crept into the fashion of long wasdted peticotes tyde with points, & had, as it seemed but one point tyed before, and comming vnuckily in my way, as I was fetching a leape, it fell out that I set my foote on her skirts: the point eyther breaking or stretching, off fell her peticoate from her waste, but as chance was, thogh his smock were course, it was cleanely: yet the poore wench was so ashamed, the rather for that she could hardly recouer her coate again from vunruly boies, that looking before like one that had the greene sicknesse, now she her cheekes all coloured with scarlet. I was sorry for her, but on I went...

Absolute genius. William Kemp, we salute you. I dub the 20th of April Kemp Day from now until forever. Amen.

Labels: renaissance, William Kemp

I think I'm going to put the beginning of an essay in here, purely to fill in some space. I'm tired and still need to watch Henry IV Part One before I can go to bed, so writing an interesting post it, regrettably, out of the question. The only thing that potentially is exciting is that having won the poetry competition, I now have to choose the next theme. Previous themes were: home; celebrity; escapism; joy; the Mona Lisa; artificial; and of course, burning. At the moment I am thinking either 'perspectives' or 'conquistadores.' I have no real reason for the latter one except I think it would be cool. Actually, I think 'local' might be good. It reminds me of that thing Auden wrote, in one of his clever little clerihews (is that an appropriate projection of the form?)

A poet's hope: to be,So yes, perhaps that. It beats the other topics at least, lots of room for the more serious types to pontificate and ruminate on too. I'm sad I won't be able to write a poem for 'local' (apparently I have decided to choose it, based on this paragraph - I'm as suprised as you!) but hopefully the theme after will be good too. Actually, just decided it's unwise to put anything from an essay which hasn't been submitted yet online, as it might cause complications with plagarism and stuff, so, as I'm on the wrong computer, no essay today. Sorry!

like some valley cheese,

local, but prized elsewhere.

P.S. - If you read this, why not produce your own 'local' poem? I would gladly offer my thoughts on anything anyone wrote!

Now, obviously my housemate was speaking in jest, but as I said at the time, his little titter at my expense isn't entirely unfounded, at least in terms of the perception of degrees. Which seems a little unfair to me, given that there are a number of subjects (Geography also springs to mind) where students can choose their degree awarded purely on a whim - there are no requirements one way or the other. Despite being a BA student, I have to admit, I think my girlfriend made the right choice - a BSc does certainly seem to hold more sway with Joe Bloggs than a BA. But how can that be, especially given that the difference in some cases is literally non-existent.

Well, I'm going to be a bit cheap here and say that it's not just one cause- the devaluation of the BA degree is a complicated thing, and not really attributable to one event. But I think it's fair to say that Labour's education policies (not in themselves a bad thing) are primarily responsible.

When Labour got into power in 1997 (gosh that seems a long time ago) they got in on the ticket of 'Education, education, education.' A drive to get 50% of school leavers into Higher Education has meant that Labour created a much-enlarged HE sector (in terms of undergraduates), and HEI's (higher education institutes) naturally accomodated for this with the introduction of additional courses, and greater capacity on existing courses. Which is all fine and dandy.

HOWEVER. A few things have changed, and I think these very short term changes have, when put in conjunction with the increased number of undergraduates entering HEI's are essentially the cause for the popular denigration of the BA. The first major blow was tuition fees. Tuition fees, and the argument which surrounded (and still surrounds - I think everyone is well prepared for a nigh on inevitable increase) actually brought into the spotlight the issue of whether students should pay for university. Previously, this had just been unquestioned, though it is with some frustration that current students find themselves treated to statements about their degree's worth, and how they ought to be contributing to it, by politicians who were gifted with a degree gratuit. When the issue came to light, there was a certain reevaluation of the relative value of the (still very substantial) subsidisation of degrees by the government. This reevaluation (particuarly during our recent recession) has put a lot of the anti-intellectual's backs up - claiming that students do nothing for three years, get essentially free grants for further drug/drink abuse, and then totter off with a useless 2:2 in a useless subject from a useless university. Sound like hyperbole? Well, here's a snippet from a comment section on a recent article on the Guardian Higher Education's website. The story, 'NUS elects new president who opposes fees hike', generated the following response from one user:

from PaulBowes01:

For those of you who think this is harsh, I'll change my opinion when I see a senior NUS figure describe students as so many of them are to those of us who don't depend on their good opinion - lazy, cosseted and financially irresponsible - rather than as the 'hard-working, poverty-stricken' victims of NUS mythology and their own endlessly self-indulgent adolescent fantasies. Sadly, from his published comments I suspect that Aaron Porter isn't the man break the mould.

So, there is definitely anger in the community, at least from some, who feel that students are essentially a waste of money for very little return. But that rather covers all degrees. BA's are struck especially hard for a number of reasons.

1. BA's are much easier than BSc's

Itself a fairly useless comment, given how the cases of Social Anthropology (sorry Anna!) and Geography remind us how arbitrary degree post-nominals are. The view stems partly from the fact that BA's do not cover 'proper' subjects. Fewer contact hours, a less visible / quantifiable style of learning and assessment come into this. Also compounding this is the invovement of former polytechnics, and increased course subscriptions due to Labour's 50% benchmark. Teaching is far cheaper than funding research (just ask HEFCE!), and so many of the additional courses, or expanded courses offered to the increased influx of undergraduates, especially at former polytechnics, which tend to be more teaching orientated than research orientated, take the form of BA's. Some members of the public view these degrees as useless, or a waste of time. I have my own gripes against certain courses, and paticularly Labour's 50% drive, but this is more about making sure students understand their employability prospects when thinking about going into such a debt-heavy thing as university. Incidentally, I might add, it's often the former poly's that do best in employability, so that's not a finger pointing at them, more a wish the government was a little bit more transparent with students over the relative merits of university, rather than selling it as a must have.

I have a bit of a problem with people who make this distinction, as it seems to me the very rhetoric of ignorance (see the BNP's listed education policies on their website: "- The abolition of fees and the restoration of full grants to university students studying proper subjects (as opposed to fake “social sciences”);"

2. BA's don't lead to any jobs

Well, in some senses undeniable - there arn't many posts which require a BA in Gender Studies, in the same way that a lawyer needs, well, a law degree (although even this isn't quite true). But this myth comes from a bizarre inflexibility from the public about the value of degrees. It seems odd to me that people can even think that a degree ought to fit cleanly with a profession as a kind of funnel-in. Not many chemists end up doing chemistry, and yet for some reason, because there is a potential career path there, regardless of how likely that path will be trodden, it equates to a more useful degree. The vast majority of graduate jobs don't require any specific degree.

Labour hasn't exactly helped the BA's cause though. In light of the recession, Labour, and particularly the snorting piglet of entitlement Mandelson, Vice Lord Admiral of seemingly every weak-wristed department in the Government, have felt compelled to show people how they are funding STEM (science, technology, engineering, maths/medicine) degrees. Because, like the BNP, they believe those are 'proper' degrees. It makes sense in some ways, we should capitalise on the potential for entrepeunerial and innovative outlets from universities. But this shouldn't come at the expense of an arts programme which is equally world-class, and equally important to the country. Think about Britain's role in in the creative media industry for example. From ringfencing funding to UCAS spaces, the Government has felt compelled to support sciences in a way they simply refuse to for the arts. Now, in a way, I don't expect anything else. We are in a recession, and someone has to take the fall. But what I do resent is someone like Mandelson making the suggestion, with empty lipservice about conserving the arts, but....I don't really trust how far forward Mandelson can think when it comes to HE policy, he seems entirely at the whims of the masses. If you need any example of that, look to the 2 year degree courses he's championing, which won't be recognized in Europe because of the Bologna process, and are more expensive for universities to provide, as well as there being evidence that students need those three years to complete their intellectual development. Nice one Mandy, with your sling-shot policy.

That;s all I have to say on the matter, except that, in all honesty, I can only see BA's falling still further int he public's opinion. Sigh. I wrote a more opinionated, commenty piece for London Student here. The paper is well worth a read - a quality publication, and well above calibre for a student publication. /biased.

Labels: BA, BSc HE Policy, degrees, revision

That golden evening I really wanted to go no farther;more than anything else I wanted to stay awhilein that conflux of two great rivers, Tapajós, Amazon,grandly, silently flowing, flowing east.Suddenly there'd been houses, people, and lots of mongrelriverboats skittering back and forthunder a sky of gorgeous, under-lit clouds,with everything gilded, burnished along one side,

EDIT: (21:35) That's really not so hot is it. Serves me right for trying to plough on regardless. Might do another one though. Or perhaps post a previous one.

Labels: Elizabeth Bishop, poetry, revision

In other words, good news! I entered a poetry competition on a student forum I use - and I won :). I wrote it in like 10 minutes as well, so I think this is a sign that I am outrageously gifted. Definitely couldn't be the number of joke entries. No way. Nope. Ok, maybe a bit. Anyway, in celebration of my my sweeping triumph, I am posting it here. The theme for the competition was 'Burning'. I took it literally, but still, I thouyght what I write was ok, minus scansion:

Waste paper thrown into the grateGO ME! *****

and left to shake in thinning heat -

it's dull opacity wavers,

turning paler, turning waxy.

The lambent flames now framed in the

taut skin, stretched till at its centre,

a glaucoma porthole now clears -

muddled shadows stoop to embrace,

released from matte recently chaste.

The paper breathes in cloying heat,

and flashes quick, a subtle bright,

(a fire flash from far away

deprived of sound by drawn out miles).

And then the point of no return:

devouring azure flames erupt -

lignin rectangle, tangled wreck,

coarse scouring tongues reduce it to a blank.

Labels: film, poetry, revision

I was thinking about it the other day, and I came up with the pretty apt comparison of them (not giving away gender!) to me was Gary to Ash. If you don't understand that reference then you are either older than me, or simply a better person, because Gary is Ash's nemesis in that most acclaimed of Japanese cultural (debatable choice of word there?) exports, Pokemon. It's summed up here There is an accent in there somewhere, but I don't know where, and I don't care enough to find out. Turns out even in procrastination apathy dogs me as much as it does whilst revising.

Labels: arch-rival, revision

The Winter's Tale Shakespeare

Henry IV Part One Shakespeare

Titus Andronicus Shakespeare

Othello Shakespeare

King Lear Shakespeare

Henry V Shakespeare

Waverley Walter Scott

Ivanhoe Walter Scott

A Burnt-Out Case Graham Greene

Collected Poems Philip Larkin

Jill Philip Larkin

Caleb Williams William Godwin

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner James Hogg

Northanger Abbey Jane Austen

Major Works John Clare

Lucky Jim Kingsley Amis

Jake's Thing Kingsley Amis

The British Museum Is Falling Down David Lodge

The Djinn In The Nightingale's Eye A. S. Byatt

The Little Black Book of Stories A. S. Byatt

The Bloody Chamber Angela Carter

Humpo and Harlequin, or, Columbine by Candlelight Thomas J. Dibdin

Major Works John Donne

The Spanish Tragedy Thomas Kyd

The Duchess of Malfi John Webster

The White Devil John Webster

The New Arcadia Sir Philip Sidney

I will update it as I go.

Labels: reading

Met Dad for lunch at Balfour's which was really lovely actually. I have walked past that restaurant so many times over the past three years, but it was good food, good service, and good vibes all round. Dad decided to show me the pictures from the Maldives, and the only way I think I can describe them is as jealousy-inducing. Unbelievable beaches and snorkelling - I can absolutely see why they love it there so much.

I also need mention probably the best, most ego-boosting event I have had for some time. Picture, if you will, the English library. I left it, on the prowl for some coffee to perk myself up a bit. As I left through the old double doors, a huge crowd appeared in front of me, waiting for some kind of conference. I made my way through, and everyone went quiet. I kept walking, and as it transpired I had no business with them the following conversation took place:

Guy 1: Why did we all just go quiet?

Girl 1: I don't know.

-Pause-

Girl 2: He must have had incredible gravitas.

How's abouts thats to bring a smile to your face?

Labels: revision

No one.

I know this is ranty, but seriously, I could have bought the DVD for that. Or enough food to last me a few days. And now I have nothing. Might meet my Dad today though, maybe he will give me some lunch or something. I feel so poor. :~(

Labels: anger

The stuff about the body has been fairly interesting though, and in the good-natured spirit of sharing academic learning, and partly as a means to recall my learning, I'll share my work a bit. I've been focussing on bodies in Shakespeare, but specifically with relation to the dialogue between interiority and exteriority. Maus' very interesting book Inwardness came in pretty useful, as did some work by last year's tutor on Othello. I'm quietly confident about it on the basis that there is plenty of bodily depictions in Shakespeare's work (and Shakespeare himself undoubtedly had it thrust upon him - from 1604 his lodgings on the corner of Muggle Street and Silver Street put him just around the corner from the Barber-Surgeons Hall, where anatomizations took place. And hopefully the body will be a useful place to go from if the exact question I want doesn't come up - there is room to talk about early modern maternities, subjectivity, and nationalism within the framework. So yeah. Go Shakespeare. Also have been reading the peerless Ivanhoe by Walter Scott. I have to say, reading what is essentially an adventure story to break work up is pretty nice.

I have traded essays with a girl off my course at her request. Hers didn't really fall into anything that I was interested in, but enjoyable to read someone else's essay as a change. Fairly similar essay style as well, which I like. Hmm. Ran into (arch-nemesis) who got an AHRC scholarship at UCL over me for the first time since the awards were announced, which was fine but...slightly unmanning. Still, I'm happy to be going to Cambridge, and at least I won't have to speak to her anymore. Plus, she doesn't appreciate Renaissance literature enough, so she clearly has no taste. Extremely unlikely, but I would so love to get funding from Cambridge and casually prop it up against her. Probably best to hope for that thin sliver of a chance on the basis of merit rather than vengenace mind.

Right - probably going to spend some time with Anna tonight, but will try and come home and do some reading - love that girl to bits, but she is terrible at waking up, and I'm in a pretty good rhythm at the moment. Maybe read some Scott before bed. I actually think if I had a child I would read him Scott - I think they're pretty good stories. I end on a passage from Ivanhoe which I found particularly, and perhaps bizzarely, touching. In it, Wamba, the Jester of Cedric, an ancient Saxon lord, puts aside his comedy to release a suitably brief lament for his master:

"Our master was too ready to fight," said the Jester; "and Athelstane was not ready enough, and no other person was ready at all. And they are prisoners to green cassocks, and black visors. And they lie all tumbled about on the green, like the crab-apples that you shake down to your swine. And I would laugh at it," said the honest Jester, "if I could for weeping." And he shed tears of unfeigned sorrow.

Labels: revision, Shakespeare

But no more today.

Sir James George FrazerThe Golden Bough

Messing with Illustrator / /homeless / The irony of househunting. / Househunting / Some old material / Favourite capture on Google Maps Street View / Idiot librarian / THIS IS NOT THAT DAY! / Confirmation (not religious) / love data? love data. /

I'm a 23 year-old student in London Cambridge London, studying English Literature Law. It's hard to really think of anything truly personal

I can put here that might give you some idea of who I am, so I will just tell you that my favourite Shakespeare play is Richard II, my favourite chocolate bar is Snickers, and I have a bit of a thing for instant coffee, especially if someone else makes it for me.

I'm interested in Renaissance Literature, Higher Education policy, and libraries.

I'm completely in love with a Scottish girl.